Listen here:

Some time ago, I went looking for Little Red Riding Hood. Turns out, she wasn’t so easy to find.

The tale begins some years back when a taxi driver, a decorated veteran of potholes, traffic jams and crooked cops, bragged to me, “Ah, I know this city like the back of my hand. I know the places no one knows. Why… I even know a street called ‘Caperucita Roja!’”

This surprised me. Buenos Aires street names aren’t usually whimsical. They are named for famous citizens, for provinces, even for cumbersome dates when something important happened. (These last I hate as I can never keep them straight.) Normally, they don’t go in for fairy tales so Caperucita Roja, which means Little Red Riding Hood, seemed improbable.

I took the cabbie’s bragging with a grain of salt. Maybe the street existed, maybe it didn’t; he might have just been trying to impress me. But I admired his professional pride. It was as if he were declaring: I am a taxi driver; this city belongs to me!

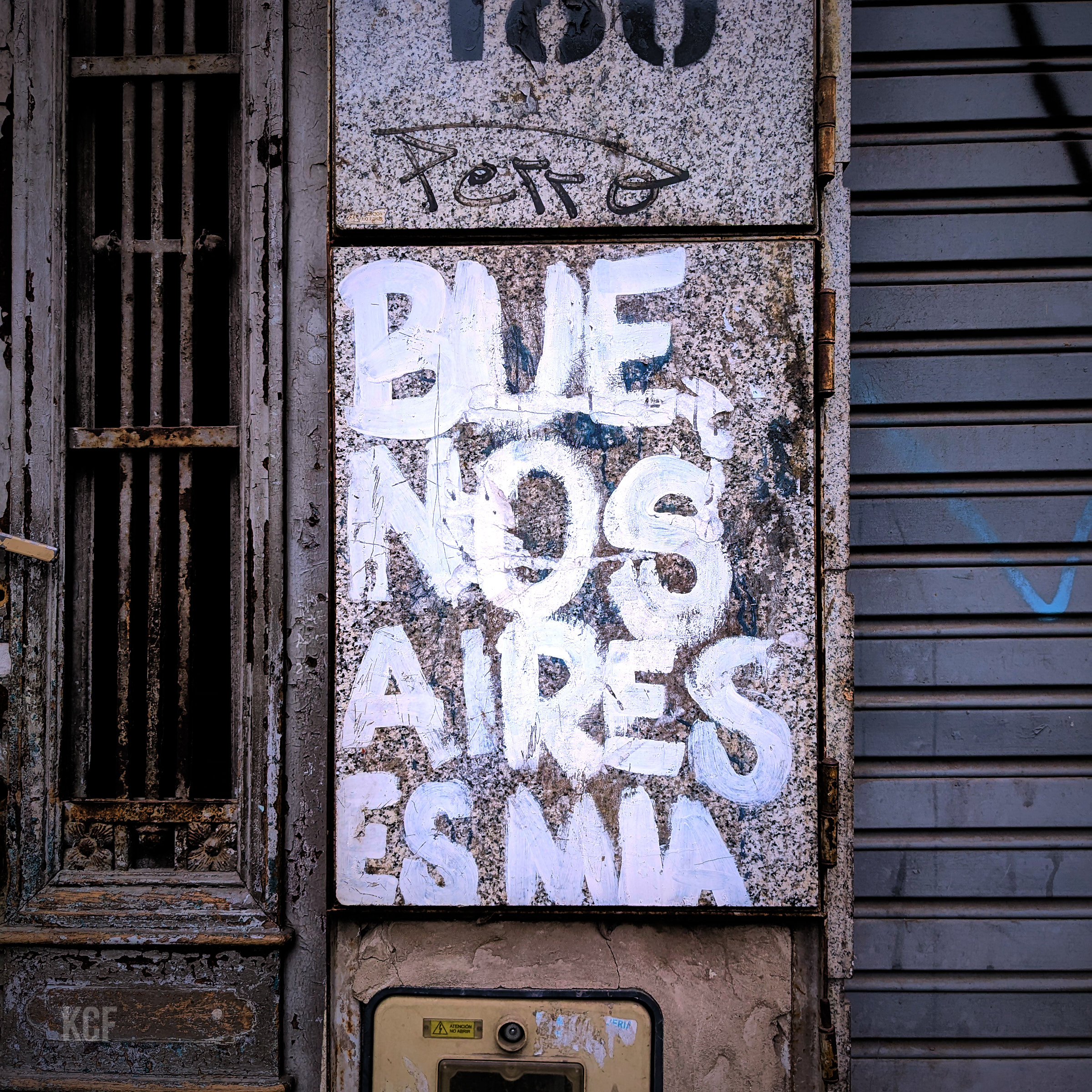

But I didn’t believe his central conceit even for a minute. Even back then, I knew intuitively that Buenos Aires was unknowable. Now, after three decades living here, I have confirmed it. I will explore her. I will adore her. I will cherish her… but I have no pretension of ever “knowing” her. Back then, it was an intuition. Now it is a tenet: Buenos Aires is a labyrinth and my life will be spent getting lost in her.

This story happened prior to cell phones let alone Google Maps. Confirming the existence (or not) of a street that seemed too good to be true had the makings of an adventure.

So a few weeks after that first tip-off, I was standing on the corner on Avenida 9 de Julio (those damn dates again!) and sticking out my arm and hailing a cab. It was Friday and I had finished work early. Spring was turning to Summer. I had my sleeves rolled up and my suit jacket thrown over my shoulder. It was a beautiful day to be free, alive and on the scent of a fairy tale.

The first two cabs I stopped had never heard of the street and I sent them off. When I asked the third, he said, “Someone’s pulling your leg.” But he cut the engine and went around to the back. He popped the trunk and got out a map book. In those days, that was how you navigated the city. With the book open on the hot black hood of his taxi, he looked under R. There were several street names ending in “Rojas,” a common last name in Argentina but no “Roja.” He was about to shut the book when I suggested he try the C’s, for ‘Caperucita.’ After all, characters from fairy tales might not be listed by their last names like ordinary civilians. Sure enough, there was a Caperucita. Not Caperucita Roja, just Caperucita.

“Well, I’ll be damned!” the taxi driver said.

We set out. At a stoplight the driver turned to me, arm over the seatback and said, “Ask 100 taxi drivers for Caperucita and I don’t think even one would know it.”

“Which street?” It was the driver of the taxi beside us who had overheard us through his open window.

“Caperucita,” my driver repeated. “Know where it is?” The other driver’s face twisted up, but he didn’t say anything. Stymied! My driver said to him, “Well, it does exist” and he told him more or less where he could find it.

As we drove off, my driver observed, “He took it as a challenge.”

“One he lost,” I said.

My driver took it upon himself to act as my tour guide, cobbling together trivia he had gleaned in his years on the streets. Passing Parque Centenario he said: “It’s round and it’s in the center of the city. And there’s a good museum where they have…um…you know…those elephants with long tales.”

“Dinosaurs?”

“Yep. Dinosaurs. Lots of them.”

All the windows were lowered to catch the breeze and the air that came through them was filled with the scent of the flowering trees that lined the avenues.

“We’ve arrived,” the cabby said. “And there is your Caperucita.” He pointed to an enamel street sign mounted on the wall of a house on the corner.

I paid the driver and thanked him for the tour.

“You learn something new every day,” he said before driving off.

Caperucita is a pasaje, more alley than street. One-block long, it is lined with trees and quiet, self-effacing, one-story houses. At the far end, a woman sat in a chair on the sidewalk watching the afternoon slide slowly down the street. As I watched her, a door opened behind me and an old man shuffled out with his own chair under his arm. He held a radio in the other hand.

“Beautiful afternoon,” I said.

He agreed and settled shakily into his chair. Inside, from a shaded patio full of songbirds in cages, his wife eyed me suspiciously. Through an open window I glimpsed one of those sturdy hospital beds opened up for airing.

Down the street, another door opened and a man emerged with two folding chairs. He set them up side-by-side then called to someone inside to bring the mate which he had left on the counter. He settled into his chair and looked up and down the street, nodding to his neighbors.

If anything were ever to happen on Caperucita they would all have front-row seats. Of course, everyone knew that this was the sort of street that nothing ever happened on. And everybody was just fine with that.

As I made my way down one sidewalk and back up the other, I felt their eyes following me.

I was dying to ask them what it was like to live on a street no one believed existed — but I held back. Like those quantum physics experiments where the act of observation changes the results, I didn’t want to upset the balance.

I tried to walk as softly as possible, minimizing the crunch of grit under my soles between those silent walls.

Before turning the corner, I looked back. A woman was coming out her front door, a folding chair under her arm and a dog beside her. I sighed with relief. Nothing had been disturbed. Everything would be okay. Everything would stay the same, forever, as in a fairy tale.

Leave a Reply